The Protected Products of Burgundy

Many of the products made in Burgundy (and France in general) have been made in the same way for centuries.

And because of that, France has very high standards for the products they produce. Only when these standards are met, specifically the how and where, with a perfect end product, do some products receive their true appellation. While it may sound pretentious and a little romantic, it holds the producer and the product to a very high and admirable standard.

France controls this by having AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée), the controlled designation of origin. This government certification ensures all wines, cheese, and certain agricultural products are produced in the region of their origin, are produced in the traditional way, and using specific ingredients. Essentially, the characteristics of the products protected are linked to their terroir. (Most countries in the EU have a similar system modeled after the French - Italy’s is DOC.)

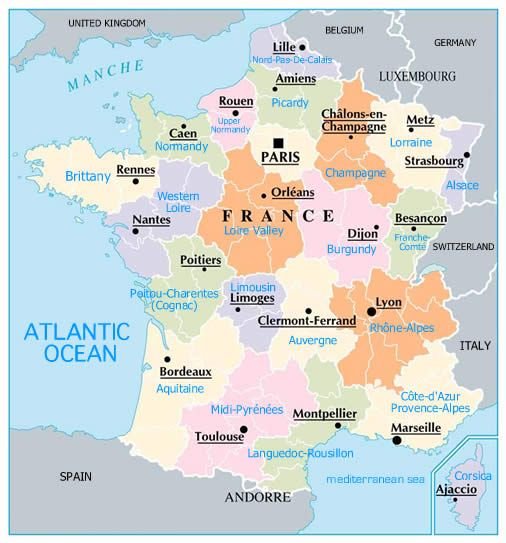

Similarly, Protected Designation of Origin (PDO - or AOP in France) protects the name of a product across all of the European Union and the United Kingdom. To gain this label, every part of the production, processing, and preparation must take place in the specific region. To use the classic example: Champagne. Meaning: you can’t call a wine made in the same style with the same grapes “Champagne” unless it’s produced in the Champagne region. So not only does the AOC protect Champagne on a national level, but the PDO protects Champagne throughout all of the EU (and the UK).

The EU adds another layer: with PGI, or Protected Geographical Indication, which protects the relationship between the specific geograpahical region and name of the product. For this, at least one of the stages of production, processing, or preparation takes place in the region. The difference between PGI and PDO are primarily how much of the products raw materials must come from the area, or how much of the production has to take place in the region.

This is all to say that the EU policies protect the names of specific products, their characteristics, geographical origin, and traditional methods. And while it may be confusing (because European countries speak different languages and the acronyms are different), it’s pretty fascinating to learn a little history about some of the protected products of Burgundy.

Charolais Beef

Charolais beef is the star of French beef. After technology replaced the need for draft animals, this white cattle breed was raised for its meat as it is able to rapidly put on weight (one of the heaviest cattle breeds). The meat is lean but buttery and tender from being grassfed from April onward.

Once again, there are many rules to award the beef as Charolais Terrior: the cows have to be raised in the Charolais region (strict borders), graze on wide natural pastures, only consume traditional supplemental fodder, and even transporting and slaughtering must be carried with particular care.

The cattle are sold around the world to 68 different countries for their meat and crossbreeding purposes which has made the Charolais-Brionnais region apply for the UNESCO’s label as a World Heritage Site to preserve and transmit this resource.

Poulet de Bresse

Poulet de Bresse are of the Bresse Gauloise breed produced within a legally defined area of the Bresse province in Bourgogne (those that are outside of the region are called Gauloise). The chickens are white with ruby red combs and blue feet. (!) The breed is the only poultry to be recognized as AOC.

To gain their AOC and PDO status, the chickens have to be raised under strict controls - including a specified amount of pasture per bird - and must pass inspection. The chickens are free range for at least four months with a low protein diet so the birds will forage for insects before they’re finished in a darkened fattening shed where they then feed on maize and milk.

From French-Gourmand Brillat-Savarin to Michelin Star Chef Georges Blanc to food writer Alan Davidson to Chef Heston Blumenthal - all have stated that this chicken is the best in the world. And the chickens even have their own website.

Dijon Mustard

Mustard has been produced since the early ages (a Roman recipe was recorded in AD 42!) as people appreciated the spicy burn of the condiment. Charlemagne advised his farmers to plant mustard, and it sprang up everywhere the Franks once ruled (now 80% of mustards seeds are imported from Canada). In 1300 there were ten moutardiers working in Paris, in 1600 there were 600. The Dukes of Burgundy, who had their residence in Dijon, issued a decree to guarantee the quailty of their city’s mustard. But it wasn’t until 1752, when Moutarde de Dijon overtook the products of other regions.

There are two varieties of plants: mild yellow mustard that produces delicate flavors and the pungent red-brown variety. The two varieties are mixed in production to obtain the desired degree of pungency. Dijon mustard does not have a PGI unless it’s seeds are produced in Burgundy and only then can it be called “Moutarde de Bourgogne.”

In France, mustard is served with both hot and cold meats. Dijon mustard is particularly suitable for cooking, marinating, or vinaigrettes.

Comté

In the Middle Ages, farmers in the Jura mountains would be cut off from the rest of the world during the long winters that could last up to six months. Originally a way of storing milk from their cows, the farmers would make hard cheeses. Because the cheese required a large amount of milk, farmers formed a cooperative (the word comtè means county so it’s appropriately named). Every day they would milk their cows and combine it with the milk from other farms to make the hard cheese that could last through the winter.

The cows themselves play a key part in the flavor of the cheese. The Montbeliarde breed produces milk that is rich in fat and casein, perfect for cheesemaking. The aroma of the cheese is mainly due to the grasses and herbs eaten by the cows.

Protected by AOC, cheese can’t be called Comté unless it is made according to specific regulations and passes an inspection that evaluates every cheese for quailty and taste before it is given the Comté logo (for the cheese that doesn’t pass, it’s prohibited from being named Comté and is sold for other purposes).

For a perfect pairing, eat Comté with a glass of vin jaune, a wine from the Jura region.

Époisses

Declared by Brillat-Savarin to be the “King of Cheeses” (and was said to be the favorite of Napoleon), Èpoisses is one of the best known cheeses from Burgundy and has been awarded AOC and PDO status. The Cistercian monks at Cîteaux Abbey began making the cheese in the sixteenth century before local farmers inherited the recipe 200 years later.

Made from the milk of the French Simmenthal, Montbeliarde, and Brune cows, the cheese is first washed with brine and then with Marc de Bourgogne, a local brandy, before maturing in a cave for at least four weeks. The aroma is pungent and intense but the flavor is nuanced. The moist rind is a soft red-orange color, and the cheese is soft, creamy, and white.

Pair with a crusty baguette and a glass of Burgundian white wine.

Anis de Flavigny

With origins as early as 1591 in the town of Semur near Flavigny, anise candies were offered presents to high-ranking guests. Aniseed at the time was used as a medicine to treat stomach problems. The Ursuline nuns became the first to surround green aniseed with a sugar shell, scented with rosewater or orange blossom water. The aniseed had first to be rolled in sugar syrup until it was completely coated, then it had to dry completely before being brushed with the next layer of sugar syrup, and so on and so on to form an almond-shaped candy.

This process used to take up to six months until it reached the desired size, making the candy rare and expensive. Even now with electric motored turbines, the process takes two weeks. Modernization of the candies has been consciously rejected by the single factory producing the candies in order to employ as many people as possible (and it’s said the recipe is the same as it was in 1591). And while the candies don’t have an AOC or DOP, they were awarded both the Intersuc Blue Ribbon (for excellent confectionery making) and the Site Remarquable du Goût (remarkable culinary heritage) award.

Crème de Cassis

Creme de Cassis is a liqueur made from blackcurrants, which have been growing in France during the 16 century and used medicinally.

Two businessmen brought the liqueur production to Dijon in 1841 but ran into the problem of not being able to get enough blackcurrants to produce the liqueur. The demand encouraged vine producers’ wives to plant currant bushes around the edges of the vineyards which in turn supplemented their housekeeping money.

Crème de Cassis is used to make the traditional Kir cocktail named after Canon Félix Kir. Kir was a priest who became famous as an opponent of the Nazis who helped thousands of Resistance fighters escape during World War II before becoming the mayor of Dijon. During the war and the years of occupation, cafés shut down and many apéritifs were on the virge of being forgotten. Kir made a point to serve blanc cassis whenever guests were in the Burgundy capital and production began to increase. The liqueur has since then secured a PGI.

Made it to the bottom? You deserve a drink!Kir Royale

Pour .5 oz of Crème de Cassis in a wine glass and top with 5 oz chilled Champagne or suitable Cremant de Bourgogne (but almost any bubble will do).